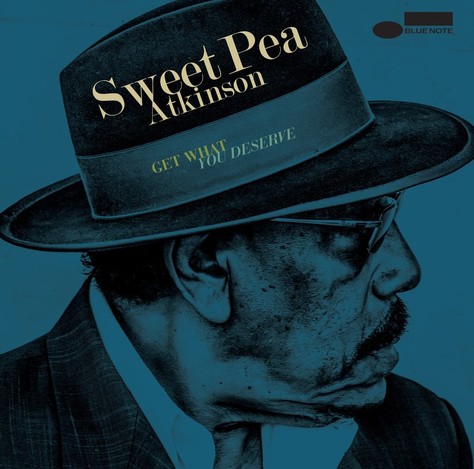

No one involved with the making of Sweet Pea Atkinson’s new album, Get What You Deserve, was really doing the math about how long it’s been since the singer’s previous solo record. And maybe that’s for the best: It’s been a staggering amount of time in the waiting. “Was it really 35 years? Oo!” says Atkinson, letting slip a bit of profanity slip as he’s informed of the exact gap. Executive producer Don Was, who also co-produced the last one back in 1982, is also surprised to hear the passage of years quantified. “That’s almost like Guns N’ Roses!” he jokes.

Time flies when you’re becoming one of the most celebrated soul singers of your generation even as you’re mostly working on other people’s projects. Atkinson’s talents have not exactly lay fallow over those decades, or his genius gone unnoticed. He’s best known as one of the lead singers of Was (Not Was), whose top 10 hit in America and the UK with “Walk the Dinosaur” made the sartorially sharp Detroit native the unlikeliest and nattiest of 1980s MTV stars. In subsequent years, he’s made his way more as a featured backup vocalist, spending a decade on the road as the most recognizable member of Lyle Lovett’s band and appearing on records by Brian Wilson, Bonnie Raitt, Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson, Bob Seger, Kris Kristofferson, George Jones, Jackson Browne, Solomon Burke, Richie Sambora and scores of others. He’s also been an intermittent lead singer for the Boneshakers. Did any of these estimable stints get him what he deserved? No, they did not.

Getting Atkinson his vast, full due in popular culture is a tall order for just one record. But for the already Atkinson-hepped, as well as, one hopes, a good amount of yet-to-be-indoctrinated members of the Sweet Pea cult, the arrival of Get What You Deserve is an occasion for deferred joy. “It’s just time for me to do something,” he says. “Everybody keeps talking about it and saying, ‘We sure wish you would hurry up!’ Well, we’ll see if they buy it when it comes out,” he laughs. “We shall see, huh? I don’t know what it means to everybody else but this album means the world to me.”

Get What You Deserve includes seven tracks produced by the great modern bluesman Keb’ Mo’ and three produced by Don Was. It was Was who signed Atkinson to a label deal, in the veteran producer’s still fairly fresh capacity as chief of Blue Note. “it’s not hyperbolic for me to tell you that one of the great honors of my life has been to work with Sweet Pea,” says Was. “One of the beautiful things about being the president of Blue Note Records is that you can give a nod to something that just touches you deeply inside-even if it flies in the face of fashion.” But, Was adds, “it was Keb’ Mo’ who really dug in with Sweet Pea and turned that nod into something brilliant.” Atkinson first met Keb’ Mo’ when he was singing backup on one of his records in the late ‘90s, and he obviously made a fast and lasting impression. Says the bluesman/producer: “Sweet Pea is one of the last great R&B/soul singers. He’s a man of charisma and style, a timeless talent who's greatly respected by his peers, and the epitome of cool. They don't make ‘em like that anymore. While listening and watching him work, like most people, you immediately know that he is his own man. I want the world to know what a kind and compassionate gentleman Sweet Pea is, adored by everyone that knows him. It's what's behind the voice that reaches the hearts of the people.”

It’s not an album that needs a lot of bolstering by famous guest stars. The only featured fellow artist is sax player Mindi Abair, who’s featured on “You Can Have Watergate,” a fairly obscure track credited to James Brown and recorded by Fred Wesley and the The JB’s in 1973; it’s a funk workout that brings some ensemble action to an otherwise Sweet Pea-centric album. Abair was a natural to bring in, since the two of them recently collaborated on a record she has coming out in conjunction with Atkinson’s side project, the Boneshakers. “She’s played with some of everybody,” says Atkinson, “and such a sweetheart. She’s a little bitty lady, but she blows the hell out of that horn. I say, how the hell do you do that?” Atkinson says, asking the same astonished question he so often fields himself.

The real featured guests on the album are ghosts, though: all the funk, soul, blues, and R&B greats to whom Atkinson is paying implicit homage, if hardly emulating. “I love blues — Johnnie Taylor and Johnny Guitar Watson and Bobby Blue Bland,” he says. This album’s “Last Two Dollars” is a song Taylor recorded late in his life, in 1996. Far better known is Bland’s 1974 hit “Ain’t No Love in the Heart of the City”; Atkinson is an even more appropriate interpreter of that particular tune than some of the artists who’ve covered it before, like Whitesnake, Crystal Gayle, and Jay-Z.

Then there’s the smoother influence from Motown and other purveyors of the vocal group sound. “I’m la singer like Paul Williams of the Temptations and Marvin Junior of the Dells,” Atkinson says, assessing his own niche as a vocalist. “When Paul Williams came along and started singing ‘Don’t Look Back’ and ‘Just Another Lonely Night’” — the latter a 1965 smash to which Atkinson brings new life on this album — “that’s when I said, ‘I want to sing like them.’ And when Marvin Junior did ‘Stay in My Corner,’ man, I ain’t heard nobody sing a song like that before in my life. That man can hold a note for so long, I go, ‘Damn, breathe, man!’ Marvin Junior, it’s hard to sing like. Paul Williams is a little easier.”

Not that he’s ever aping anyone in particular. “I ain’t copying anybody,” says Sweet Pea. “I can’t. Just give me the song and I’ll sing the shit out of it, but it ain’t gonna sound like them. It sounds like me.” He’ll offer a candid assessment of his strengths and limits: “There’s one thing I don’t have: a tenor. I have a baritone and a second tenor. I wish I could get way up there in the air, but I can’t. Hit them high notes? Oh, man, if I could, I could do a lot with them. I can’t. I just sing what I’m singing.” Not to worry — anyone who’s ever heard the rarefied, natural grit in Atkinson’s voice, and just how high he can actually take that baritone when the occasion calls, has never complained they wished he were going falsetto on them instead.

Observes Was, “There’s something about him that just wasn’t made for these times – maybe Brian wrote that song for him. He’s younger than the raspy voiced soul crooners that we worship, like Otis Redding and Wilson Pickett although I think Marvin Junior from the Dells is really Sweet Pea’s guy. By the time we were all making records together, a new kind of soul singing had come into vogue: Prince and Rick James and a higher voiced, clearer, different kind of phrasing. So he was a marketing anomaly, in a way. But it’s a good time for him now - his voice is so unique. You don’t have to AutoTune Sweet Pea, and there’s really no point in punching in words here and there. He’s never going to sing it the same way twice, ever. There’s nobody else around like him.”

While Keb’ Mo’ did all the initial production for the album, Was wrapped it up by getting Atkinson to sing two Freddie Scott hits, “Are You Lonely for Me Baby” (which was also a hit in the ‘60s as a duet by Otis Redding and Carla Thomas) and “Am I Grooving You.” The producer was inspired by driving around with Keith Richards and hearing his tape of Scott songs, the latter of which was covered in the ‘70s on a Ron Wood solo album that Richards played on. Was had his reasons for steering Atkinson in this direction. “Keb’ Mo’ did an amazing job of manifesting Sweet Pea’s vision,” says Was. “and Sweet Pea envisions himself as a lover and a soul crooner…which is all well and good!” he laughs. “But I think part of his greatness is as a belter, so we just cut a couple more songs to really show off that side.” Album complete, then, as Get What You Deserve gives us an Atkinson who’s a lover and a bit of an R&B fighter.

Was first came across Atkinson one fateful night in Detroit in the late ‘70s. “I was working with a band called Energy,” Atkinson recalls — a band made up of UAW workers — “and one of the guys who owned the rehearsal hall went over there and told Don, ‘You gotta go hear this guy.’ He came over and, man, he went crazy.” Not just over the voice, as Was recalls it, but the whole package. “I just remember there was goofy, bright orange shag carpeting on the walls, and I was coming out of a dark room at 3 in the morning, and Sweet Pea was dressed from head to toe in an orange ensemble that started at his shoes and went all the way to the hat. Everything was orange, and not just any orange but a perfectly matched shade. You know, a lot of work went into matching the socks to the hat! And in the bright lights of this hallway with the orange shag carpeting, he looked like fire,” Was says, cracking up at the memory. “He was blinding. And he was the most entertaining cat. You know, he’d already had a couple of lifetimes leading up to singing in that auto workers band.”

Before the ‘70s were up, with Was’ help, Atkinson had landed a deal with Portrait Records, which fell apart before they ever made a record, thanks to Epic dissolving the label. Eventually, in 1982, Was and his partner David Was would get around to recording Atkinson’s first solo album, Don’t Walk Away, for Island. The songs the Was brothers wrote for that were weird enough that many people consider it a Was (Not Was) album, in spirit, although it took a turn toward the normal with a cover of Burt Bacharach’s “Anyone Who Had a Heart.” That solo debut, recently given a digital re-release, “kind of slipped through the cracks,” Was says, “but it’s got some hawkish devotees (laughing) around the world. The people who know that record are super into it.”

But before Atkinson’s solo debut in ’82 came the first Was (Not Was) album, recorded at the turn of the decade. If you would imagine that it took some getting used to for an aficionado of the Temptations and Dells to cotton to the bizarre lyrical ethos of Was (Not Was), you’d be right. “The first song Don wanted me to do was ‘Woodwork Squeaks and Out Come the Freaks’,” Atkinson recalls. “I didn’t want to do it, because I thought that I was too goddam cool. I didn’t do it, either. And then I end up singing ‘Knocked down, made small, treated like a rubber ball’!” he laughs.

Was’ version of the story lines up. “We gave him the first version of ‘Out Come the Freaks,’ and the opening line was ‘Like Little Michael on a motorcycle with leather pants and a leather brain, he ain’t ever been the same since Vietnam.’ And Sweet Pea looked at it and he said, ‘I ain’t singing this shit!’ and he walked out. And I remember chasing him down the street saying, ‘No, just give it a try! You’ll sound great!’ as he got in his car and he drove away. Because of that, we called Sir Harry Bowens to sing that song, and that’s why there were multiple lead singers in Was (Not Was)! He would have been carrying the show except for refusing to sing that song that day. But he never refused any songs after that,” chuckling at how Atkinson’s competitive spirit led him to accept some of the group’s most outrageous lyrics.

After a long tour opening for Dire Straits in ’92 that Atkinson still fondly recalls, Was (Not Was) essentially ceased to exist as a touring and, eventually, recording unit. But that was hardly an end to the Was/Sweet Pea collaboration, as Atkinson was brought in on untold numbers of the sessions Don Was got hired for as a newly in-demand producer, starting with Bonnie Raitt’s Nick of Time and continuing on with everybody from Dylan to Michael McDonald to Iggy Pop.

Which raises the question: How did somebody with such a ridiculously distinctive lead-singer voice ever enjoy such a long and fruitful career as part of the backing chorale? As Keb’ Mo’ says, “He has a huge voice that really stands out rather than blends in. But Sweet Pea has figured out how to do both, depending on the situation he's in.”

“He’s not necessarily a blender,” agrees Was, trying to explain the dichotomy. “He can blend, but he’s got to work at it, because background singers are supposed to stay in the background and not cut through. If you hear Mick Jagger singing background harmony on ‘You’re So Vain,’ he leaps out because he’s so audiogenic. And Sweet Pea’s got that going on too. There were times we used to have to push him really far back in the room,” Was laughs. “He’d have to get way off-mic to do stuff.”

For his part, Atkinson doesn’t give that much thought to what makes him such an able harmonizer as well as frontman, saying: “I can sing with anybody as long as they don’t sing opera.”

Now he’s back in front, where he more than arguably belongs. It’s another fruition of that fateful moment 40 years ago when Atkinson and Was crossed paths at 3 in the morning in a Detroit rehearsal hall, allowing America to get to enjoy the talents of a singer who’s really off any kind of timeline. “It’s the whole package, man,” says Was. “When I first laid eyes on him, he wasn’t famous, he wasn’t rich, but he was larger than life. And that personality and presence comes across in his singing. If you put on the first song on this album and you hear this guy start roaring, it’s a larger than life voice because that’s who he is.”

He’s still personally bigger than any kind of known reality to Was, 40 years later. He tells a story. “One time we played in Glasgow at the university, and it was a really wild crowd. You could actually see the balcony moving and shaking; it was terrifying. Then everyone went to a packed pub near the gig, and I’d never seen a debauched audience after-party like this. A crowd of drunken hooligans came out and started breaking beer bottles on the pavement, clearly trying to flatten the tires of our bus. David and I looked out the window at this mob trying to vandalize the bus, and we were cowering in the window like, ‘Oh, man, what are we going to do.’ Sweet Pea was changing out of his suit; he didn’t have a shirt on, just had these silk pants and his shoes and, of course, his hat. And he didn’t think twice. He grabbed the fire extinguisher, held it up like a fucking billy club, and went out there and made this mob of drunk guys sweep up. He was outnumbered, like, 20 to 1, but no one questioned him! And with the authority that he commanded, and the fact that he wasn’t bluffing, these intoxicated maniacs got under the bus and with their bare hands swept away the broken glass so we could drive off… with David and myself, watching him take command of the situation. I just remember admiring him so much in that moment — and so much more over the years. He was just fearless and righteous, and the things he stood up for were the right things, and he didn’t think twice about it. He’d say anything to any motherfucker, if he saw something wrong happen. It’s not just that he sang the way we wished we could sing. He’s the guy we wished we could be.”